Śaṇmukhī Mudrā: The Gateway to Inner Silence

In the rich tradition of yoga, Śaṇmukhī Mudrā stands as a profound technique for sensory withdrawal and inner awareness. As Geeta Iyengar explains in

Geeta Iyengar’s narrative begins with her own path into yoga, which wasn’t a straightforward one. After a severe illness in her childhood, she describes a pivotal moment when her father gave her an ultimatum: “From tomorrow onwards no more medicines. Either you practise Yoga or get prepared to die.” Yet this dramatic beginning evolved into a nuanced teaching relationship that she later describes in depth.

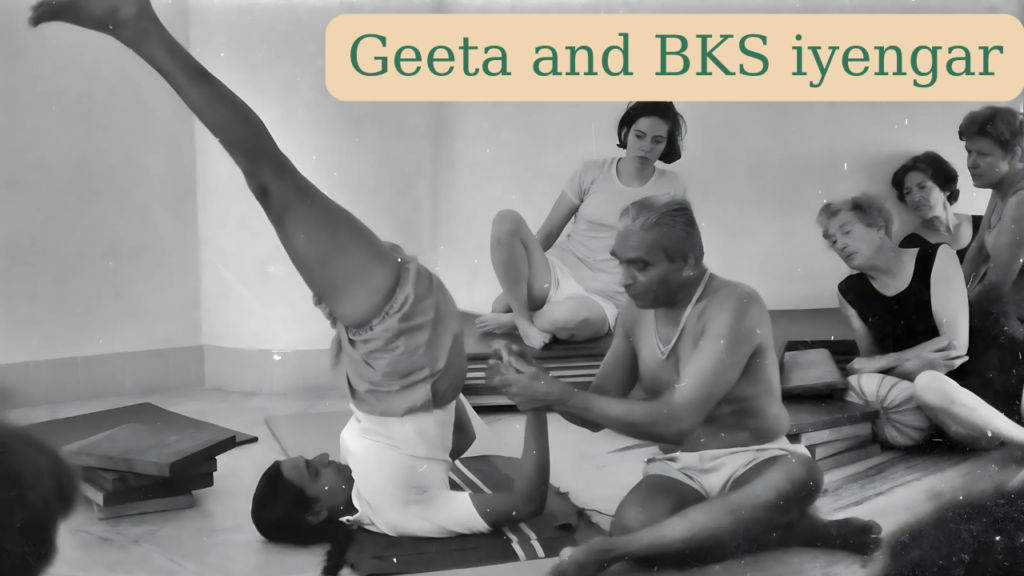

“Rarely does a pupil find the Guru and the Father in one person,” she writes, highlighting the unique complexity of her situation. This duality required careful navigation, which her father managed by maintaining clear boundaries. As she notes, “While teaching me Yoga, he treated me not as his daughter, but as a pupil.” This distinction was crucial in establishing a proper guru-shishya relationship despite their family bond.

Her description of B.K.S. Iyengar’s teaching method reveals the essence of their guru-shishya relationship. He was “very exacting as a teacher” and “a stickler for discipline and a taskmaster,” yet she emphasizes that “his ways are gentle persuasion and not stern reprimand.” The relationship was founded on freedom of choice, as she notes: “Never did he inflict his opinions or thoughts on me, nor did he try to impose the Yoga Sadhana on me. There was no compulsion or duress. Yoga was my free choice.” Yet within this freedom, there was an expectation of dedication, as “He expects discipline and keen attention from his pupils. Is not Yoga Sadhana the greatest of disciplines?”

Geeta places this personal experience within a broader historical context. She describes how in the Vedic period, women had access to gurukula education and studied various disciplines including yoga. This tradition changed over time, as “Gradually woman’s position became a subsidiary one… The Gurukula and thread ceremony were denied to her.” This historical perspective makes her own guru-shishya relationship even more significant, as it represents a return to the inclusive tradition of the Vedic period.

Her experience offers a modern interpretation of the guru-shishya relationship that maintains its essential elements while adapting to contemporary needs. This is particularly relevant given her observation that today’s women must balance multiple roles and face “all-round competition.” The guru-shishya relationship she describes is one that can accommodate these modern demands while preserving the depth of traditional teaching.

Geeta’s journey comes full circle as she herself becomes a teacher. In writing this book, she acknowledges both her father’s role as guru and her mother’s influence: “It is impossible for me to repay the debt of gratitude of my father and mother who became my Gurus, except to follow forever and sincerely the path of Yoga taught by them.” This statement shows how the guru-shishya relationship extends beyond the immediate teacher-student dynamic to become part of a continuing lineage of knowledge transmission.

Through these various aspects of her account, Geeta Iyengar presents a comprehensive picture of a guru-shishya relationship that honors tradition while embracing modernity, one that balances discipline with autonomy, and maintains professional boundaries even within family relationships. Her experience provides valuable insights for understanding how this ancient teaching tradition can be meaningfully practiced in contemporary times.

In the rich tradition of yoga, Śaṇmukhī Mudrā stands as a profound technique for sensory withdrawal and inner awareness. As Geeta Iyengar explains in

“Yoga is the rule book for playing the game of Life, but in this game no one needs to lose.” This profound statement from

“The rhythm of the body, the melody of the mind, and the harmony of the soul create the symphony of life.” With these poetic

Agi Wittich is a yoga practitioner since two decades, and is a certified Iyengar Yoga teacher. Wittich studied Sanskrit and Tamil at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, completing a PhD with a focus on Hinduism, Yoga, and Gender. She has published academic papers exploring topics such as Iyengar yoga and women, the effects of Western media on the image of yoga, and an analysis of the Thirumanthiram yoga text.