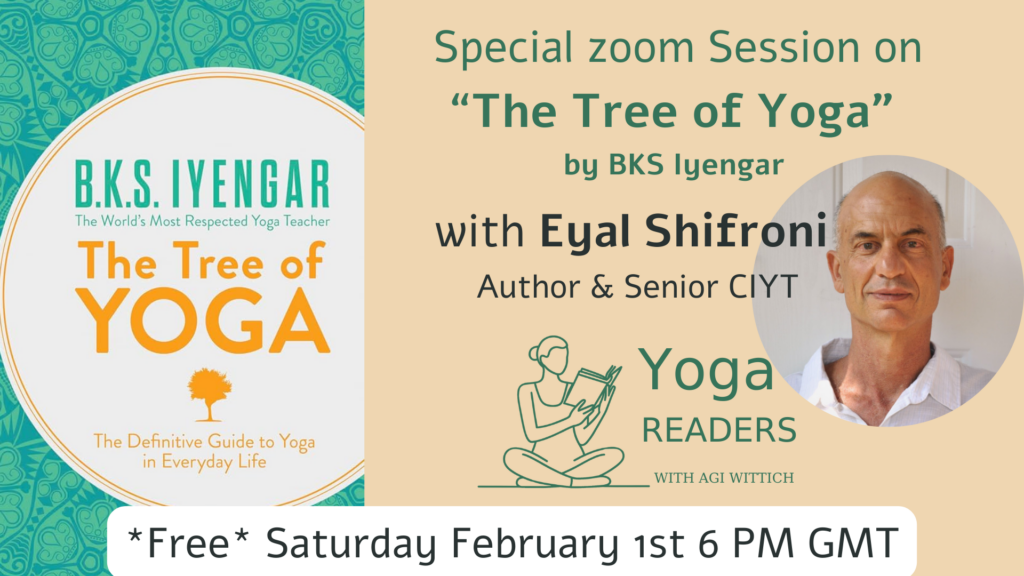

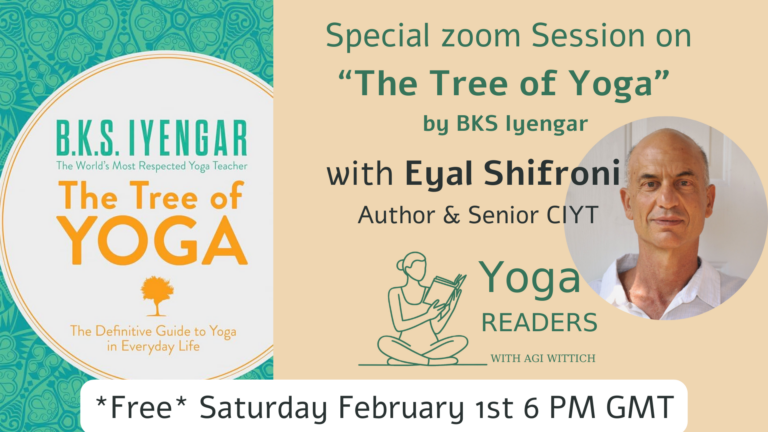

Eyal Shifroni brings over 45 years of yoga practice and teaching experience to this special session. As the director of the Iyengar Yoga Center in Zichron Ya’akov, Israel, he has dedicated his life to deepening and sharing yoga wisdom since 1978. In this session, Eyal drew from his extensive experience as both a teacher and author, he shared unique insights about the intersection of yoga practice and literature.

These are my thoughts following the special session with Eyal Shifroni, a senior Iyengar yoga teacher with over four decades of practice experience, that spoke with the Yoga Readers’ community.

The Power of Books in Yoga Practice

When asked about the role of books in yoga practice, Shifroni offered a thoughtful perspective:

“Books are like storage of knowledge that is given in an orderly fashion that you can always come back to and read again and again and learn more and more. Like, let’s take Light on Yoga. I have a few copies. One in my studio, one in the living room, one in my bedroom. And I refer to it very often.”

He emphasized that while books serve as important references, they cannot replace direct instruction:

“Yoga is also a connection relationship between a teacher and a student. You learn, you get knowledge from the students, but not only knowledge, you get inspiration. You see his example, his practice, his demonstration, the way he teaches, the way he behaves in the class. So all of this is a lesson. This is something that you learn which cannot be given by a book.”

This balance between written knowledge and direct transmission reflects the traditional approach to yoga, where personal guidance complements textual study. How might this balance shape your own approach to learning? Does your practice incorporate both the wisdom found in texts and the nuanced instruction that comes from in-person teaching?

The Tree of Yoga: A Unique Voice

Shifroni spoke with particular fondness about B.K.S. Iyengar’s “The Tree of Yoga,” which he translated into Hebrew. What distinguishes this book, in his view, is its authenticity of voice:

“When I read it, I can really hear Guruji. I refer to him as Guruji. I really hear his voice and his way he used to talk. Because it’s actually like a collection, it’s edited collection of his talks. So the language is really, really his own language, his own words and his own way to express himself.”

He contrasted this with “Light on Life,” which, though valuable, was co-written with American writers and therefore lacks the direct, conversational quality of “The Tree of Yoga.” This observation raises interesting questions about authenticity in yoga literature. What is gained or lost when a teacher’s words are filtered through collaborators or editors? How important is it to preserve the original voice and expression of yoga masters?

The Journey to Authorship

Shifroni’s own journey as an author began simply—he wanted to organize his scattered workshop notes for personal use. What started as a personal project unexpectedly blossomed:

“I wrote it in Hebrew and I printed 300 copies. And I came with them to a workshop, to some international workshop that was in Israel. And they all sold out.”

His first book on using chairs in yoga practice resonated deeply with practitioners worldwide:

“It really went into a niche that was not populated by other books. And a lot of people really liked it. And then I got so many enthusiastic feedbacks. So it gives me the motivation to continue the work and to write more books.”

This humble beginning has led to an impressive collection of works translated into numerous languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French, Polish, Russian, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Japanese. Shifroni’s global impact demonstrates how addressing a specific need within the yoga community can have far-reaching effects.

Props as Enhancers of Practice

One of Shifroni’s most significant contributions to yoga literature has been his extensive work on using props. He explained that his approach differs from therapeutic applications:

“The main thing that I wanted to convey is how props can enrich your practice. So even if you can do the pose without the prop, using the prop, you can learn something new about the prop, about the pose. Because the props can give you different effects that make different actions that you have to do in the asana very clear.”

He offered a specific example:

“We say that we need to take the femur bone into the sockets in Utthita Trikonasana. And we need to maintain the load on the back leg. So if you raise the front leg on a chair or even on a block, you feel that the femur bone of the front leg is going much better into the socket. And the back leg, you feel heavy because you change the geometry of the pose.”

This perspective challenges the notion that props are only for beginners or those with limitations. Instead, Shifroni presents them as sophisticated tools for deepening understanding and experience of asanas. How might this change your relationship with props in your practice? Could props be not just aids but teachers in their own right?

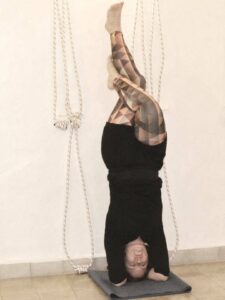

Yoga in Nature: A Different Experience

Perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of Shifroni’s work is his advocacy for practicing yoga in natural settings. He described his experience practicing on the beach:

“When I go out to nature, I feel really different. In the studio when I practice, sometimes it takes me like half an hour even more to really get into the practice, to become quiet mentally and to open the body. And in the beach, where I practice most of the time, it’s instantaneous. I mean, I go there and immediately I feel the wind, the water, the air, the fresh air… All the elements of nature.”

He discovered that natural elements could serve as props:

“I found out so many ways to use the sand as a prop. And it’s actually more flexible than the artificial props we use because you can make from the sand different shapes, you can use different levels, you can dig small holes, you can use slopes.”

This creative approach invites us to reconsider our relationship with both practice environments and props. How might your practice change if you occasionally moved it outdoors? What natural elements in your environment might enhance your yoga experience?

Mind-Body Connection: The Psychophysical Lab

Shifroni also discussed “The Psychophysical Lab,” co-written with Ohad Nachtomi, which explores the philosophical problem of the mind-body connection:

“Experientially we feel that we are one unit personality. You know, body and mind are connected in so many ways. And when I want to move a limb, I can move it. But philosophically it’s not so easy to account for it.”

The book offers practical explorations:

“Sometimes you change something in the body and you observe the effect on the mind and sometimes you change something in the mind like the focus, point of focus, and then you see how it affects the experience of the pose.”

This investigation into one of philosophy’s central questions—how mind and body interact—provides a fascinating bridge between Eastern and Western approaches to consciousness. Have you noticed specific connections between mental focus and physical experience in your own practice? How might conscious experimentation with these relationships deepen your understanding?

Preserving Yoga’s Integrity

A participant raised concerns about how yoga is evolving in the modern world, particularly with the rise of “spa yoga” and “supermarket yoga.” Shifroni acknowledged these challenges:

“Yoga is a way of life with the ethics, with the yama niyama, with all the other four limbs after pranayama. It’s part of yoga, not only the asanas. And many people even don’t practice pranayama, they just do the asanas, they just treat it as gym culture.”

Yet he remains optimistic:

“In Hebrew there is a saying… it means that when you start to do something, even if the reason is that you want to lose weight or to get fit, maybe it will lead you to the more deep aspects of the practice of yoga.”

This tension between accessibility and depth, between popularity and authenticity, continues to shape yoga’s evolution. What responsibility do practitioners and teachers have in maintaining yoga’s integrity while welcoming newcomers? How can we balance tradition and innovation?

Reflections for Your Practice

As we consider Eyal Shifroni’s insights and experiences, several questions emerge for our own practice:

- How do you balance textual knowledge with direct instruction in your yoga journey? Consider the ways different learning modes complement each other.

- What role do props play in your practice? Are they merely aids, or could they be tools for deeper exploration?

- Have you experimented with practicing in natural settings? How does environment affect your experience of yoga?

- How do you navigate the relationship between mind and body in your practice? What specific techniques help you observe their interaction?

- In what ways do you connect with yoga as a comprehensive life philosophy beyond the physical postures? How might this broader understanding transform your practice?

Eyal Shifroni’s journey reminds us that yoga continues to evolve while remaining rooted in ancient wisdom. His work with props, nature, and philosophical inquiry demonstrates how innovation can deepen rather than dilute tradition. As practitioners, we each contribute to yoga’s ongoing story through our sincere engagement with both its timeless principles and its contemporary expressions.

“Yoga transcends cultural differences while respecting individual experiences. When I teach internationally, I’m constantly reminded that the fundamental human experience of embodiment—of being present in a body that breathes, moves, and feels—connects us across all apparent differences.”

>click on the image to watch the session recording<