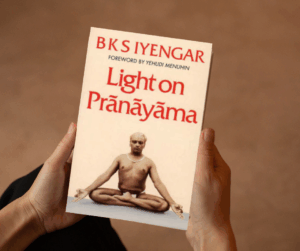

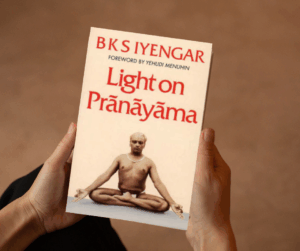

Closing Gathering for Light on Pranayama

Date and Time: May 24, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) As our Yoga Readers cycle on B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Prāṇāyāma comes to completion, we

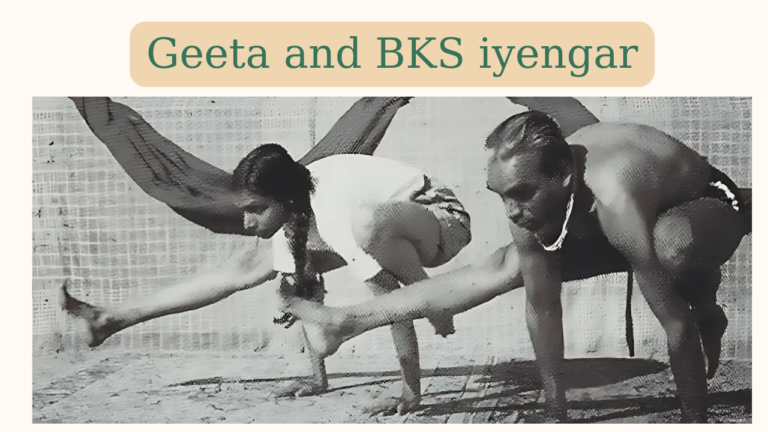

The ancient tradition of guru-śiṣya in yoga represents one of the most profound methods of knowledge transmission in spiritual practice. Through Geeta Iyengar’s remarkable book “Yoga – A Gem for Women,” we gain unique insights into this sacred relationship, particularly through her personal experience of having B.K.S. Iyengar as both her father and guru.

“Rarely does a pupil find the Guru and the Father in one person,” Geeta writes, offering us a glimpse into her extraordinary position. This dual relationship required careful navigation, which her father managed with remarkable wisdom. “While teaching me Yoga, he treated me not as his daughter, but as a pupil,” she notes, demonstrating how the sacred guru-śiṣya bond transcended even familial ties.

The historical context Geeta provides enriches our understanding of this tradition. In the Vedic period, she tells us, both men and women had access to gurukula education, studying various disciplines including yoga. A Gurukula is a traditional Indian educational system where students live with their guru in a residential learning environment, often in the guru’s home or an ashram. This ancient educational model dates back thousands of years and represents one of the oldest educational systems in the world. In a Gurukula, education extends far beyond academic subjects to encompass character development, spiritual growth, and practical life skills. Students receive personalized instruction from their guru while also participating in the daily responsibilities of maintaining the household or ashram. The intimate teacher-student relationship allows for transmission of knowledge that goes beyond textbooks, including oral traditions, ethical values, and experiential wisdom. Historically focused on Vedic learning, Sanskrit studies, and spiritual disciplines, some modern Gurukulas continue this tradition while adapting to contemporary educational needs, preserving a holistic approach to learning that integrates intellectual, physical, emotional, and spiritual development. Geeta continues, this inclusive tradition gradually changed as “woman’s position became a subsidiary one… The Gurukula and thread ceremony were denied to her.” This historical perspective makes her own guru-śiṣya relationship even more significant, representing a return to the ancient inclusive traditions.

What makes Geeta’s account particularly valuable is her description of how the guru-śiṣya relationship can maintain its sacred essence while adapting to modern times. Her father was “very exacting as a teacher” and “a stickler for discipline,” yet his approach was one of “gentle persuasion and not stern reprimand.” Most importantly, she emphasizes the element of choice: “Never did he inflict his opinions or thoughts on me, nor did he try to impose the Yoga Sadhana on me. There was no compulsion or duress. Yoga was my free choice.”

Her journey began dramatically when her father declared, “From tomorrow onwards no more medicines. Either you practise Yoga or get prepared to die.” Yet this stark beginning evolved into a nuanced teaching relationship that balanced discipline with autonomy. This balance is crucial in understanding how the guru-śiṣya tradition can thrive in contemporary times while maintaining its profound spiritual depth.

The relationship she describes embodies the true meaning of “guru” – the dispeller of darkness. Through her father’s guidance, she not only recovered her health but discovered her life’s path. Her experience shows how the guru-śiṣya relationship extends beyond mere instruction to become a vehicle for complete transformation.

Perhaps most poignantly, Geeta’s story comes full circle as she acknowledges both her parents as gurus: “It is impossible for me to repay the debt of gratitude of my father and mother who became my Gurus, except to follow forever and sincerely the path of Yoga taught by them.” This statement reveals how the guru-śiṣya relationship creates an unbroken chain of knowledge transmission, each student potentially becoming a future teacher.

Through Geeta’s account, we see how the guru-śiṣya tradition remains vital and relevant in modern yoga practice. It demonstrates that this ancient relationship can adapt to contemporary needs while preserving its essential elements of guidance, discipline, and spiritual transformation. Her experience shows us that the guru-śiṣya relationship, when properly understood and practiced, continues to be one of the most powerful vehicles for transmitting the profound wisdom of yoga.

Date and Time: May 24, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) As our Yoga Readers cycle on B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Prāṇāyāma comes to completion, we

A global reading journey with B.K.S. Iyengar’s classic on the yogic art of breathing January – May 2026 on Sundays 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal

Date and Time: January 18, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) In this new Yoga Readers cycle we will be reading B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on

Agi Wittich is a yoga practitioner since two decades, and is a certified Iyengar Yoga teacher. Wittich studied Sanskrit and Tamil at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, completing a PhD with a focus on Hinduism, Yoga, and Gender. She has published academic papers exploring topics such as Iyengar yoga and women, the effects of Western media on the image of yoga, and an analysis of the Thirumanthiram yoga text.